This Time Last Year, I Was Singing My Friend to Death

Toronto has been choking on heat this week.

It’s sticky. Relentless. Angry.

It doesn’t feel like Canadian June.

It feels like Texas.

Which is fitting, I guess.

Because everything this week feels like Texas.

The air. My skin.

The way my brain keeps spitting out timestamps.

One year ago today, I was eating Takis and stale cookies from a prison vending machine.

One year ago today, the Board of Pardons and Paroles said no to mercy.

One year ago today, I hoped we had more time.

There was no more time.

It was horrible.

Yet, I want to remember every second.

The shape of his laugh. The cold of the holding cell. The way the tube curled around his arm.

The way his voice remained (mostly) steady as he apologized.

This week is a landmine.

Every hour detonates something.

And Thursday, June 26th is the big one.

One year since the state of Texas executed Ramiro Gonzales.

One year since I walked out of that chamber and started trying to figure out how to begin again.

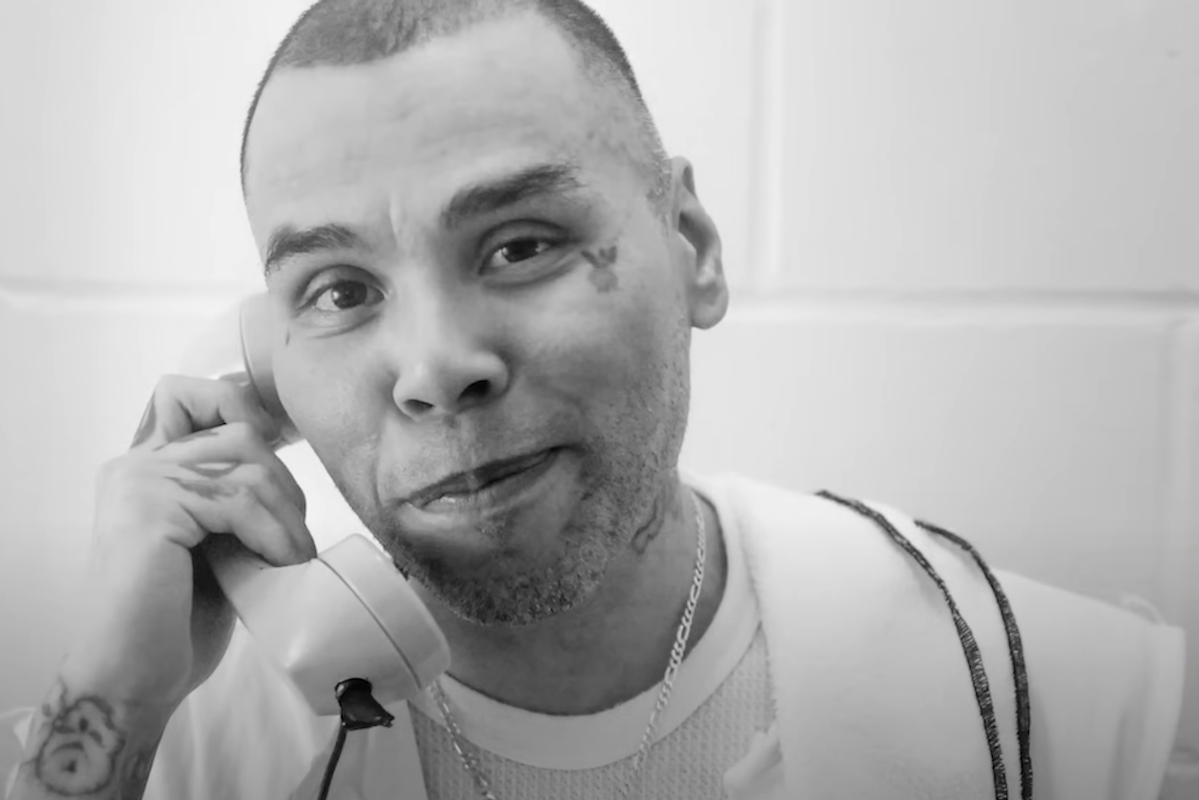

Ramiro, as he was

I’d known Ramiro for more than a decade.

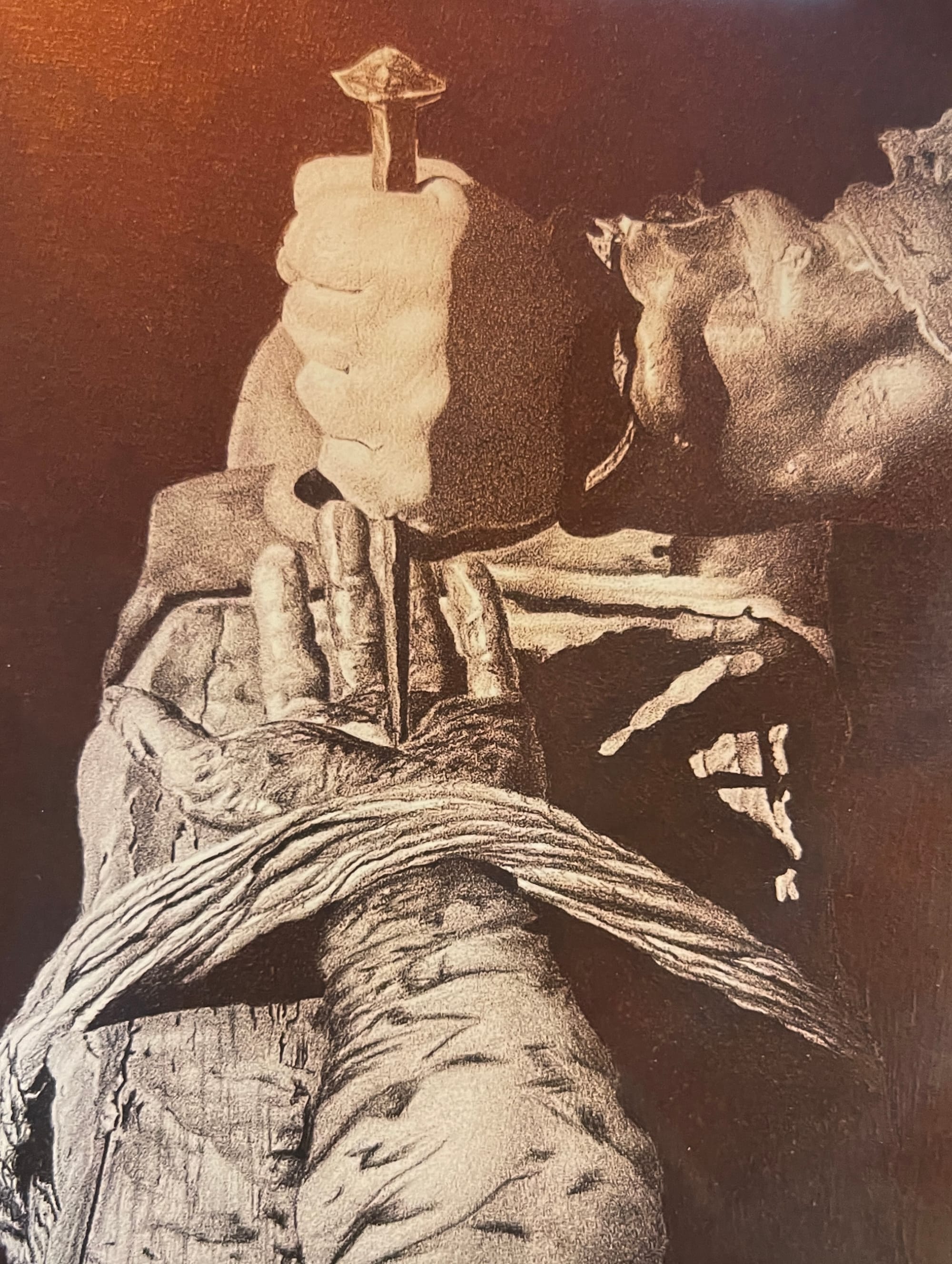

My friend was an artist.

His drawings were beautiful and sharp. What he could create with a pencil and a ballpoint pen was astounding.

Everything he did had intention.

His letters were more like epistles.

He gave away soup and coffee to guys who didn’t have anybody on the outside.

He’d pray for everybody. For the guards. Even for the people who hated him.

And always, always, for the family of the woman he killed.

He never stopped hoping they’d forgive him — not for his sake, but for theirs.

Because he knew what hate does to the soul.

He’d lived it.

He wasn’t perfect.

He was funny, sharp-tongued, and occasionally a pain in the ass.

He’d been locked up since he was a teenager, and some parts of him never aged past that.

He’d get upset if I didn’t write back fast enough.

I’d be juggling kids, church, work, death...

and he’d be stewing because I hadn’t answered his last letter.

Time moved slower for him. That cell was the whole world.

Sometimes I had to remind myself:

He doesn’t get to go outside. He doesn’t get a break.

Too often, his life was a concrete box and a typewriter.

I have a lot of guilt about the times I was slow to respond.

But he was mine. And I was his.

He called me Mana — short for hermana. Sister.

He teased me constantly.

A few years ago, I sat down across from him in the visitation room, picked up the phone, and the first thing he said…

not hello, not how are you…

was…

“What’s going on with your hair?”

“What do you mean?”

He grinned. “When did you become an old lady, Mana? You’ve got tinsel now!”

Then he laughed so hard he had to place the phone down,

and his cousin in the background shouted, “You’re being mean!”

That was Ramiro. Equal parts affection and audacity.

He loved the Houston Astros and gave me endless grief about the Blue Jays.

I pretended to care about baseball just to keep up.

He knew I didn’t. He thought it was funny.

When my dad was dying, he sent me card after card. Handwritten, always.

Every birthday. Every Christmas. Every Mother’s Day.

He never missed one. Not once.

We cried together about what he did.

He told me everything. The rape. The murder. The guilt.

He would’ve done anything to undo it.

But life doesn’t work like that.

There’s no un-killing.

But still, he found love.

He told me he didn’t know how to love before.

That being loved helped him love himself. And then love others.

His final words before they killed him were, “I love you, Mana.”

Just a man facing death, telling the truth.

Walking him home

Most spiritual advisors don’t write clemency petitions.

Part of one, anyway.

Ramiro’s attorneys brought me in because they wanted to make a spiritual case,

to show the Board what kind of man he’d become.

What faith had done. What love had done.

What he had done to become someone new.

That he was so much more than the State was admitting.

So I wrote.

I tried to fit the fullness of him into a format with margins.

Tried to make his transformation legible to people who didn’t believe he was worth saving.

I failed.

On the day of his execution, I was given his personal property.

I held his whole life in a suitcase that was too heavy to fly home with.

Shoes. Letters. photographs. The ashes of a life Texas didn’t want to remember.

At 3 p.m., I sat with him in the holding cell at the Huntsville Unit.

Just the two of us.

We sang together . Old hymns. The ones we both knew.

The vocabulary of our common ground.

We shared communion.

It was make-do.

Grape juice in a plastic cup. A broken cracker.

A sacred meal between bars with two hours to go.

He told me I mattered.

That the attorneys mattered.

That his family mattered.

He asked me to keep checking in on everyone after it was over.

He prayed for the tie down team and the executioner.

At 4:30 p.m., he got the news: the Supreme Court had refused to intervene.

We both knew that was it.

There would be no reprieve.

As they came to move me to another holding area, he looked at me through the bars of the cell.

“I love you,” he said.

“I’ll see you soon, Mana.”

The moral tension

So many people don’t know what to do with a story like this.

They want it to be one thing or the other.

Was he a monster or a martyr?

Was I deceived or devoted?

It’s easier to simplify than to see someone whole.

The truth is that Ramiro did something horrific.

He was also kind, hilarious, thoughtful, redeemed.

Both are true.

Loving Ramiro doesn’t mean I don’t grieve for the woman he killed.

It doesn’t mean I don’t think about her family.

It doesn’t mean I don’t sometimes get angry at him, too.

Compassion isn’t a limited resource.

It doesn’t run out when you use it on someone “undeserving.”

That’s not how love works. That’s not how God works.

I can cry for what Ramiro did and still believe he shouldn’t have been executed.

I can hold him at the end and still name the violence he caused.

None of that cancels out the other.

I also know Ramiro wouldn’t have done what he did if he’d been raised in a world that gave a damn about him.

If he’d had a safe home.

If someone had held him instead of hitting him. Raping him.

If Texas hadn’t churned him through the machinery of neglect and abandonment before he ever picked up a weapon.

The state that killed him is the same one that helped shape him.

All the while pretending it had no part in the story.

Ramiro was responsible.

But he wasn’t alone.

The system failed him long before he failed anyone else.

I’m not trying to excuse Ramiro.

I’m trying to make sure the story doesn’t get flattened into “he got what he deserved.”

(He didn’t.)

This is about love.

And remembering.

Because forgetting is what lets it happen again, and again.

This isn’t a clean story.

There’s blood and beauty tangled together.

There’s love that makes no sense.

There are now two deaths that didn’t need to happen.

What a waste.

The weight of grief and trauma

After the execution, my body stopped knowing what to do.

For weeks, I played this stupid game in my head: Is it grief, or is it trauma?

Is the crying because I miss him , or because I watched him die?

Is the nausea because I loved him , or because I stood in that room and didn’t stop it?

(Moral injury is a brutal companion.)

I wasn’t like that in the chamber.

In the chamber, I was calm.

Singing Psalm 46 while the poison moved through him. Holding my ground.

But once I was home, my nervous system wouldn’t shut off.

I was jittery. Couldn’t sleep. Couldn’t sit still.

Everything felt dangerous.

I didn’t fall apart until it was safe to. Even then, it was only a little bit, and only for a short time.

Our bodies are loyal to survival, not to healing.

Back in Toronto, everything felt wrong.

Most people were kind. But nobody here knows what an execution smells like. Nobody here understands what it does to your insides.

I kept thinking , I need to be in Texas.

I need to be where people get it.

I wanted to sit in the dark with Ramiro’s attorneys, drinking bad whisky and swapping stories in the language of the bereaved.

Be with the only people who knew what it was to lose him this way.

Instead, I was surrounded by regular life. Grocery lists. Emails. Weather complaints.

I didn’t belong.

And then there were the sounds.

The first week I was home, lying awake in bed, and my husband started snoring.

I nearly puked.

Because it sounded like that.

It’s what a body sounds like when it’s being poisoned by pentobarbital.

It’s what Ramiro sounded like as his body shut down.

Plastic tubing. The smell of antiseptic.

Any trace and I’m back there again. Watching. Frozen. Helpless.

I still dream about it.

Dream that he’s calling for me. Begging me to help.

And I don’t.

I freeze.

I always freeze.

Even in my dreams, I fail him.

I started staying home.

I stopped reaching out. Let friendships drift.

It wasn’t anyone’s fault. I just didn’t have the energy to translate what happened.

Instead, I wrote.

A lot.

Like, a lot a lot.

Because I was afraid I’d forget.

Writing was the only way to get it out of my bloodstream.

I needed to name what happened.

To make it real.

To say: this happened. To him. To me. To us.

Of course the world didn’t stop.

I’ve seen enough injustice to know better.

But I stopped.

Or at least slowed down.

And I’m still trying to begin again.

Where was God?

People ask me if I sensed God in the execution chamber.

And I tell them yes.

But not the God I wanted.

Not the God I prayed for.

Not the God who swoops in last-minute with a pardon and a glowing light and says, not today, child. Not this one.

I wanted that God.

I don’t even believe in that God , but I wanted them anyway.

Desperately.

Instead, I got the God I actually believe in.

The one who doesn’t intervene but shows up anyway.

I think Ramiro felt that God.

He said he wasn’t afraid of death,

although he was afraid of dying.

Said he knew where he was going.

And I believed him.

I don’t think God saved him.

But I think God held him.

At that point, it had to be enough.

On June 26, 2024, I let myself believe in heaven.

Not quite the pearly gates version.

I pictured beers.

High fives.

All the friends he’d said goodbye to over the years as they were led out of the prison.

Jesus in a ball cap, saying, “You made it, man.”

I don’t know if any of that’s true.

But I needed it to be.

Because if God wasn’t there, then neither of us stood a chance.

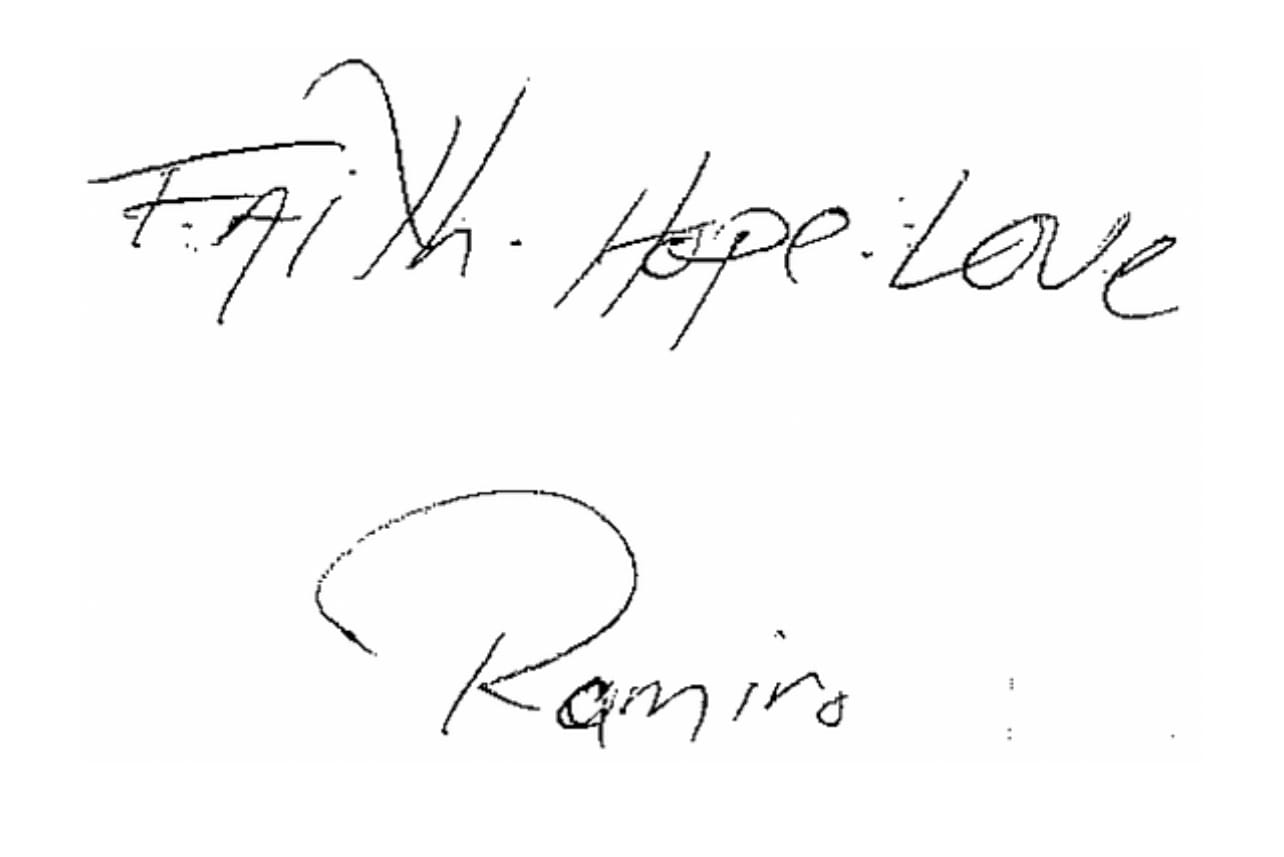

Every letter Ramiro ever sent me ended the same way:

A nod to 1 Corinthians.

A promise.

A prayer.

I got it tattooed on my wrist after he died.

My first and only tattoo.

Black ink, simple. Permanent.

He wasn’t innocent.

But he was mine. And I was his.

And love like that changes you.

People can cause deep harm.

And still be worthy of love.

Redemption doesn’t erase the past.

But it does matter.

I wear the words so I can tell his story.

So when someone asks me if he mattered, I can point to my wrist and say: he still does.

Faith. Hope. Love.

Ramiro believed in all three.

And in the end, he was right.

The greatest of these is love. 🦢

Member discussion